Scoping Your Document

This resource document provides tips to focus documents—from progress reports to peer-reviewed articles—in terms of the document’s purpose, audience, and length. Focusing your document appropriately helps enable your audience to use your document as you intend. This resource document aligns with the lessons and techniques in The Writing System (TWS, 2020) .

When you analyze your audience and purpose, consider answering the following six questions to help you limit the scope of your document. Resist providing too much information, which hinders your audience’s ability to read and use your document.

Question 1

What result do you want from your document?

Question 2

Who is your audience?

Question 3

How does your audience use your document?

Question 4

What does the audience need to know?

Question 5

Does the audience have a high or low level of knowledge about the topic?

Question 6

Does the audience believe you or need proof?

Determine How to Partition Your Document for Multiple Audiences

If you have more than one audience (see your answer to Question 2 on the first page), you must partition your document for each audience (TWS pages 24-25). You have three options:

- Write separate documents. For example, you might write a factsheet for an audience of patients who decide whether to implement your recommendations, and you might write a journal article for an audience of researchers who must master the subject matter. You report the same findings but in different ways.

- Break your document into sections. For example, you might set aside one section of a journal article as Implications for Researchers and one section as Implications for Health Care Providers.

- Use front or back matter. For example, you might write the core document for one audience and write an executive summary or an appendix for a separate audience.

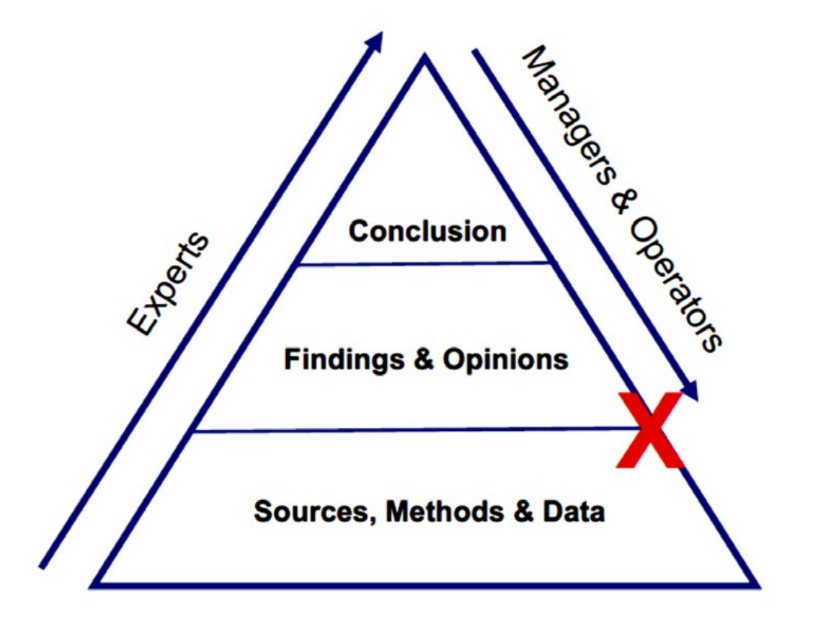

This graphic (TWS page 16) can help you think through the placement of your information compared to your audience’s needs. Limit the information to what your audience needs to know in a particular section of your document. Think through whether the audience for a particular section has a high level of knowledge, so you can use technical language, or a low level of knowledge, so you should define terms, give examples, draw analogies, and provide pictures. Operators will need little or no supporting data, whereas experts want data, followed by findings and conclusions. In contrast, managers want recommendations or conclusions first, then rationale with little or no supporting data.

The full citation of the sources referenced above are in the pop up below.

Writing an Annotated Bibliography

This resource document provides guidance on the utility of annotated bibliographies in developing their written products. It explains the purpose of an annotated bibliography, different types of annotated bibliographies, information that should be included in the annotated bibliography, and citation formats used for annotated bibliographies.

What is the step-by-step process?

There are three basic steps to complete your annotated bibliography: choosing a source, summarizing the source, and assessing relevance of the source.

- Choosing a source. The first step of the process is to locate and record citations that you think might contain valuable information on your topic. This requires reading the source material and evaluating the perspectives presented and the background of the author. You should also evaluate the material based upon similar work that covers your topic.

- Summarizing the source. Your summary should be a concise explanation of the central idea or thesis of the work, the population being studied, the methodological approach, and the author(s) findings or conclusions.

- Assessing relevance of the source Be certain that the source is relevant to your field of study. Evaluate the research methodology presented and its relation to similar studies in your field. In most instances, it is necessary to consider timeliness as much as the conclusions drawn from the source and explain how this work expounds upon your topic.

Annotated bibliographies have a variety of formats and styles.

Your citation style should be formatted in the bibliographic style of the publication outlet. For instance, if the journal uses American Psychological Association (APA) style format, then you should follow conventions for APA style citations. Depending on the style format, the structure of your citations will vary. The annotation should begin as a paragraph following the citation entry.

Example annotation using APA 7th edition

Ssemata, A.S, Gladding, S., John C.C. et al. (2017). Developing mentorship in a resource-limited context: a qualitative research study of the experiences and perceptions of the Mackerere University student and faculty mentorship programme. BMC Med Educ 17, 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0962-8

This article highlights results from interviews with mentors and mentees following their participation in a mentorship program. Six key themes were identified for mentorship: (1) define the role of the mentor; (2) top desired characteristics in a mentor and mentee relationship are trust and mutual respect; (3) overlap in mentor and supervisor roles can lead to ethical challenges; (4) the process of identifying a mentor, (5) current barriers to effective mentoring; and (6) recommendations for the future development of mentoring programs.

The full citation of the sources referenced above are in the pop up below.

Tips for Applying a Health Equity Lens to Evaluative Writing

This resource document provides tips to apply a health equity lens when writing for evaluation. This guide emphasizes the use of inclusive language to eliminate stereotypes and maintain respect and dignity when referring to people who are disproportionately affected by cardiovascular outcomes. We also recommend referring to your organization’s Health Equity style guide, if one exists, when writing for evaluation.

Step 1: Fostering Use of Intentionally Inclusive Language

- Understand the importance of intersectionality.

- Use disaggregated data to ensure that the experiences of individuals with intersectional identities are not missing or overlooked.

- When communicating about disparities, be sure to emphasize the value of ensuring that everyone has an equal opportunity for health and that reducing disparities contributes to the common good and benefits all; explain that disparities can be prevented and recommend solutions.

- When describing long-standing systemic health and social inequities:

- Avoid implying that a person/community/population is responsible for increased risk of adverse outcomes.

- Contextualize within the social determinants of health framework.

- Review content for unintentional stereotyping, stigmatization, or blame.

- Use inclusive language to avoid unintentionally excluding certain groups (e.g., use gender-inclusive language if not referring to a specific sex or gender group – e.g., chairperson instead of chairman, avoid using pronouns or use they or he/she).

Step 2: Structure Evaluative Writing to Improve and Inform Policy

- Define that you are evaluating cardiovascular outcomes in specific populations.

- Be clear about the criteria used for the evaluation.

- Identify the methodology employed and any limitations.

- State the implications of the evaluation findings in terms of health inequity and health policy.

- Include relevant policy impacts and opportunities for policy.

Step 3: Use Thoughtful Science Communication for Dissemination

- Ensure that the materials you provide are accessible to individuals with disabilities.

- Make sure your findings are amplifying the voices and issues of concern for the people, groups, and communities you have studied.

- Disseminate findings to relevant audiences, including policy makers, communities and their partners, public health officials, and health care providers.

Health Equity Style Guides:

Preferred Terms for Select Population Groups & Communities | Gateway to Health Communication | CDC

GLAAD Media Reference Guide – 11th Edition

Changing Terminology:

Latina, Latino, or LatinX? Here’s the history, and why Latine might work better. – Vox

Narratives and Language | Prioritizing Equity – YouTube

Health Equity 101:

Roots of Health Inequity | NACCHO

Advancing Health Equity in Chronic Disease Prevention and Management | CDC

Frameworks:

BARHII: FRAMEWORK — BARHII – Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative

Concepts, Tools and Frameworks for Building and Evaluating Equity

Tools for working with data:

CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index (SVI)

Racial Equity Data Road Map | Mass.gov

Other:

Teaching Race: Pedagogy and Practice | Center for Teaching | Vanderbilt University